Introduction

Bulimia Nervosa, commonly known as bulimia, is a severe eating disorder that affects millions worldwide. This disorder is marked by a dangerous cycle of overeating and purging, where individuals consume large quantities of food in a short period and then engage in compensatory behaviors including purging, over-exercising, or abusing laxatives to avoid gaining weight. While bulimia primarily affects adolescents and young adults, anyone can develop it regardless of age, gender, or background. Due to its complex relationship with both physical and mental health, bulimia remains a challenging disorder to diagnose and treat. Addressing it requires a nuanced understanding of its symptoms, causes, and impacts, as well as the available treatments. By raising awareness and providing accurate information, we can help those affected find the support they need to pursue recovery and well-being.

Overview of Bulimia

A brief description of bulimia as an eating disorder and its impact on physical and mental health.

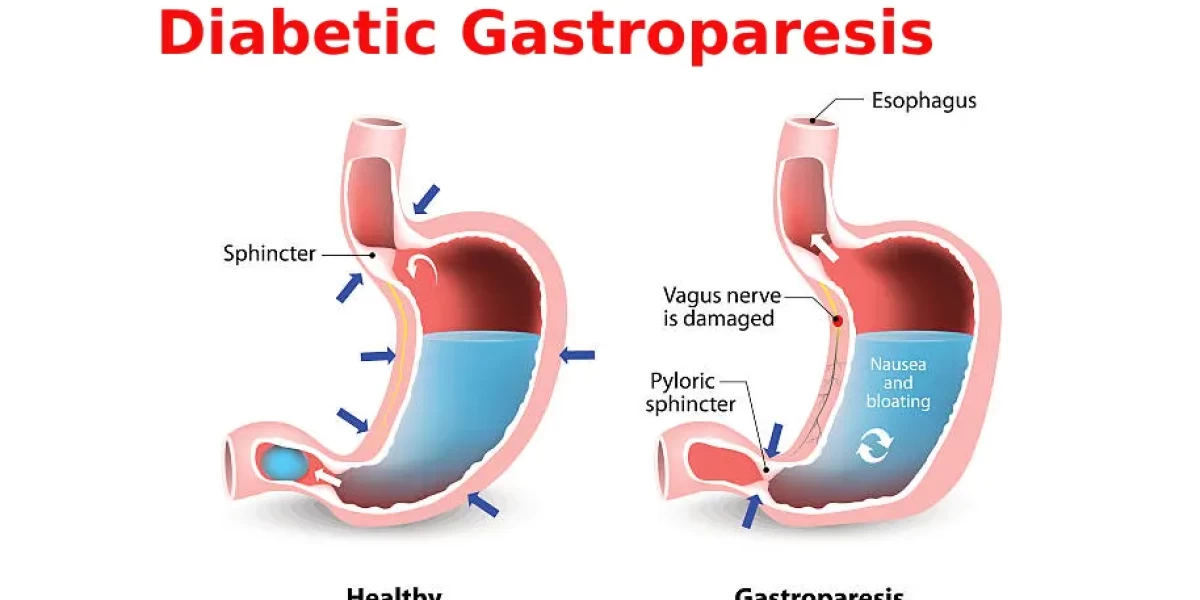

Bulimia is classified as an eating disorder, characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by extreme measures to counteract the caloric intake. These compensatory actions typically involve purging through vomiting or the use of laxatives, but may also include fasting or excessive exercise. The consequences of these behaviors extend far beyond issues related to weight. Physically, bulimia can cause serious damage to the digestive system, teeth, and esophagus due to frequent exposure to stomach acid. It can also disrupt electrolyte balance, leading to heart complications, fatigue, and muscle weakness. On the mental health front, bulimia is often accompanied by anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and an intense fear of weight gain. This makes the disorder especially challenging to overcome, as individuals frequently struggle with both the physical and psychological symptoms simultaneously. Understanding these facets is essential in providing comprehensive support to those in need.

Why Understanding Bulimia is Important

Explanation of the disorder’s prevalence and significance of raising awareness.

Bulimia is more common than many realize, with a significant percentage of individuals—predominantly females but also many males—affected by the disorder worldwide. In fact, studies suggest that approximately 1.5% of young women and 0.5% of men will experience bulimia at some point in their lives. The effects of this disorder are often hidden, as people with bulimia may maintain a “normal” weight, making it difficult to detect from external appearance alone. Due to its covert nature and complex symptoms, bulimia can go undiagnosed and untreated for years, leading to long-term health consequences and often increasing the risk of mortality. Raising awareness about bulimia’s signs, symptoms, and available treatments is critical to helping individuals recognize the disorder in themselves or others and seek timely intervention. Moreover, education on this issue fosters empathy and reduces stigma, creating a supportive environment for those affected to seek help and recovery.

What Is Bulimia?

Definition of Bulimia Nervosa

Clinical definition and classification within eating disorders.

Clinically, bulimia nervosa is classified within the spectrum of eating disorders in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition). It is primarily defined by recurrent episodes of binge eating, where individuals feel a lack of control over their eating behavior, followed by compensatory behaviors meant to avoid weight gain. These binge-purge cycles must occur at least once a week over three months to meet the diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa. The disorder is distinct from anorexia nervosa, where severe food restriction and an intense fear of weight gain are predominant; however, both disorders share a similar focus on body image and weight control. Recognizing the clinical definitions and classifications can help in identifying bulimia early and distinguishing it from other eating disorders, enabling proper treatment.

Types of Bulimia

Breakdown of common types, including purging and non-purging subtypes.

Bulimia is generally divided into two primary subtypes: purging and non-purging. The purging subtype is the more well-known and involves behaviors such as self-induced vomiting or the misuse of diuretics, laxatives, or enemas following binge episodes. These methods are used as a direct means of expelling consumed calories and are typically the most physically harmful due to the harsh impact of stomach acid on the digestive system and other organs. In contrast, the non-purging subtype involves compensatory behaviors that do not include direct expulsion of food but instead rely on other methods such as excessive exercise or prolonged fasting to offset calorie intake. While the non-purging subtype may seem less harmful, it can still lead to severe physical complications and psychological distress. Both types of bulimia are serious and warrant treatment to address both the behavioral patterns and underlying issues contributing to the disorder. Understanding these subtypes is vital for healthcare providers and loved ones to recognize the diversity of behaviors associated with bulimia and offer appropriate, targeted support.

Signs and Symptoms of Bulimia: A Comprehensive Guide

Bulimia Nervosa is an eating disorder that significantly affects physical health and psychological well-being. People with bulimia may feel trapped in a cycle of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors, like purging, to prevent weight gain. Bulimia can be challenging to recognize as those affected often hide their behaviors. Here, we’ll explore the various signs, symptoms, causes, and risk factors of bulimia to shed light on this complex condition.

Physical Symptoms of Bulimia

Physical symptoms of bulimia can vary widely based on the frequency and intensity of binge-purge cycles. These symptoms often emerge due to the strain the disorder places on the body. Observable physical signs may include:

-

Fluctuations in Weight: Individuals with bulimia might undergo rapid weight changes as a result of cycles of binge eating and purging. While some may maintain a normal weight, others may see weight gain or loss over time.

-

Digestive Issues: Repeated vomiting can lead to acid reflux, stomach pain, and a constant feeling of fullness. It can also irritate the esophagus, leading to sore throats and, in severe cases, esophageal ruptures.

-

Swelling in Facial Features: Bulimia may lead to facial swelling, especially around the cheeks and jaw. This swelling is often due to inflamed salivary glands resulting from repeated vomiting.

-

Dental Problems: The acidic nature of vomit can erode tooth enamel, leading to sensitivity, discoloration, and frequent cavities. Dentists are often the first to notice these signs in patients with bulimia.

-

Skin Changes: Chronically low nutrient levels may cause skin to become dry and brittle. Bulimic individuals may also develop calluses on their knuckles, known as “Russell's sign,” caused by using their fingers to induce vomiting.

-

Chronic Fatigue and Muscle Weakness: Malnutrition and the strain of purging behaviors can lead to chronic fatigue and muscle weakness, often limiting physical activity and productivity.

These symptoms are often warning signs for friends, family, and healthcare providers to notice and take action before the disorder causes more severe damage to health.

Behavioral and Emotional Symptoms

The emotional and behavioral patterns of bulimia are often as prominent as the physical symptoms and may provide insight into the individual’s internal struggle with the disorder. Behavioral and emotional signs include:

-

Secrecy Around Food: People with bulimia may hide food or avoid eating with others to conceal binge episodes. They may also excuse themselves to the bathroom right after meals, where they may purge.

-

Obsession with Body Image and Weight: People with bulimia frequently feel significant body dissatisfaction and an intense fear of gaining weight. They may engage in frequent "body checks" by looking in mirrors, weighing themselves, or measuring body parts.

-

Mood Swings: The guilt, shame, and stress surrounding eating habits can result in drastic mood swings. People with bulimia may oscillate between feelings of euphoria after purging and depression or anxiety soon after.

-

Engaging in Excessive Exercise: Compensatory behaviors aren’t limited to purging through vomiting. Many individuals with bulimia also adopt compulsive exercise routines to offset caloric intake, often feeling distressed if they’re unable to exercise.

-

Use of Laxatives or Diuretics: Some individuals may use laxatives, diuretics, or other medications to induce bowel movements or fluid loss, further complicating their relationship with food and health.

-

Social Withdrawal: People with bulimia may become more isolated, avoiding social gatherings to avoid judgment or questions about their eating behaviors. This isolation can reinforce their struggle, creating a cycle of loneliness and increased bulimic behaviors.

How Symptoms Manifest Over Time

Without intervention, the symptoms of bulimia can become progressively more severe. In the early stages, symptoms might be mild and intermittent, but over time, binge-purge cycles become more intense and ingrained in daily life.

-

Progressive Organ Damage: Chronic vomiting can severely damage the gastrointestinal tract, leading to gastric rupture, chronic acid reflux, and damage to the esophagus. Electrolyte imbalances from purging can also affect heart function, potentially leading to irregular heartbeats or even heart failure.

-

Worsening Psychological Symptoms: Left untreated, bulimia often leads to worsening anxiety and depression. The individual might feel ensnared in the binge-purge cycle, amplifying feelings of despair and helplessness.

-

Increased Frequency of Episodes: As the disorder progresses, individuals may find themselves binge eating and purging more frequently, with episodes occurring multiple times per day. This escalation can make it even harder to break free from the cycle.

-

Risk of Relapse: Relapse is frequently observed among individuals with bulimia, even after they have sought help. Relapse can occur due to stressful events, unresolved emotional triggers, or insufficient support systems, emphasizing the need for ongoing treatment and support.

Causes and Risk Factors of Bulimia

Understanding the causes of bulimia involves examining various factors, including biological, psychological, and environmental elements. Here’s a look at these contributing factors:

Biological and Genetic Influences

Inherited genetic traits can elevate the risk of developing bulimia. Studies suggest that individuals with family members who have bulimia or other eating disorders are at a higher risk of developing the disorder themselves. Biological factors, including imbalances in serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, may also contribute. Some individuals may be biologically predisposed to impulsive behaviors, making them more susceptible to bulimic behaviors like binge eating.

Psychological Factors

Certain mental health conditions and personality traits are strongly associated with bulimia. For example, individuals with anxiety disorders, depression, or obsessive-compulsive tendencies may be more vulnerable to developing bulimia. People with low self-esteem, perfectionistic tendencies, and poor impulse control are also at higher risk, as they may turn to binge eating and purging as coping mechanisms for dealing with overwhelming emotions.

Environmental and Cultural Influences

Social pressures, particularly in cultures that idolize thinness, play a significant role in the development of bulimia. Media portrayals of the “ideal” body shape, peer pressure, and societal expectations can cause individuals to feel inadequate or unattractive, leading them to unhealthy eating patterns. Additionally, certain environments, such as competitive sports or industries that emphasize appearance, may contribute to increased risk.

Co-Occurring Conditions

Bulimia frequently co-occurs with other mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse. For example, individuals who have experienced trauma may develop bulimia as a means of managing unresolved emotional distress. The presence of co-occurring conditions often complicates treatment, as both the eating disorder and underlying mental health issue need to be addressed for a successful recovery.

How Is Bulimia Diagnosed?

Bulimia nervosa, an eating disorder marked by episodes of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors like purging, is a serious condition requiring accurate diagnosis for effective treatment. Professionals employ a combination of medical and psychological evaluations to establish a bulimia diagnosis, focusing on specific criteria, reliable assessment tools, and ensuring that qualified healthcare providers make the diagnosis. Understanding the diagnostic process is essential for those affected, as it lays the groundwork for appropriate treatment and recovery planning. In this article, we’ll explore the key steps in diagnosing bulimia, the professionals qualified to make the diagnosis, and factors that influence the course of the disorder and the potential for recovery.

Criteria for Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa are defined by mental health guidelines, specifically in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). According to the DSM-5, individuals with bulimia must experience recurrent episodes of binge eating. Binge eating episodes involve eating a much larger quantity of food than most people would consume in a similar period, often accompanied by feelings of loss of control. To be diagnosed, individuals must engage in inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as vomiting, misuse of laxatives, fasting, or excessive exercise, in response to binge eating episodes. These behaviors must occur at least once a week for a period of three months. The diagnosis also requires that self-esteem or body image is significantly impacted by body weight and shape.

Psychological assessments also play a vital role in diagnosis. Professionals examine symptoms beyond eating patterns, looking for underlying anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive behaviors often associated with bulimia. This mental health examination, alongside physical assessments, ensures the individual’s broader well-being is taken into account, recognizing that bulimia often occurs with coexisting disorders. In addition to clinical criteria, health professionals assess the impact of bulimia on daily life, relationships, and academic or job performance to understand its full scope. Identifying the psychological motivations behind bulimia and the physical and social implications helps provide a more comprehensive diagnosis.

Methods for Diagnosis

Diagnosing bulimia typically involves a combination of evaluation methods, including clinical interviews, self-report questionnaires, and physical assessments. The clinical interview is a fundamental component, allowing professionals to gather a thorough history of eating behaviors, thought patterns, and emotional triggers. Structured interviews, such as the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE), are commonly used to understand the severity and frequency of symptoms. This tool provides a standardized way to measure bulimia's impact and helps identify specific symptoms, including binge-purge cycles, body image concerns, and feelings of guilt.

Additionally, self-report questionnaires, such as the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), are valuable in the diagnostic process. These standardized tools allow individuals to reflect on their eating patterns and mental health, giving professionals insight into symptom severity. Physical assessments are equally essential, especially since bulimia can lead to numerous health complications, including electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal issues, and cardiovascular strain. Blood tests and other diagnostic measures help identify these potential health risks, providing a clearer picture of the disorder's physical impact. The combination of psychological evaluations, self-assessments, and physical exams ensures a well-rounded diagnosis, addressing both the mental and physical dimensions of bulimia.

Who Can Diagnose Bulimia?

Bulimia nervosa is a complex mental health disorder that requires a diagnosis from qualified healthcare professionals, typically involving psychiatrists, psychologists, or licensed mental health counselors. Psychiatrists, who are medical doctors with specialized training in mental health, are equipped to diagnose bulimia based on both psychological and physical symptoms. They can prescribe medication if needed and offer insights into the biological aspects of the disorder. Psychologists, who hold advanced degrees in mental health, are skilled in conducting psychological assessments and utilizing structured interviews, but they do not prescribe medication. In many cases, clinical social workers and licensed mental health counselors can also diagnose bulimia. These professionals have extensive training in mental health counseling and are skilled in providing therapeutic support.

Often, a multidisciplinary team approach is employed, bringing together specialists to offer a comprehensive diagnosis and treatment plan. Primary care doctors may also play a role in diagnosis, particularly in recognizing physical symptoms and making appropriate referrals. Nutritionists or dietitians may participate to assess dietary patterns, although they do not diagnose bulimia themselves. Each of these professionals contributes a unique perspective, and their combined expertise ensures that diagnosis is accurate and holistic, addressing the varied aspects of bulimia and setting the stage for effective treatment.

Duration of Bulimia

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Bulimia

Bulimia can vary significantly in duration, ranging from short-term cases lasting a few months to chronic, long-term forms persisting for years. Short-term bulimia may arise due to specific triggers, such as life changes or stressors, and might resolve with timely intervention. In these cases, individuals may engage in bulimic behaviors sporadically, and with appropriate support, they can break the cycle relatively quickly. However, chronic bulimia, lasting several years or even decades, often stems from deeper psychological issues, such as long-standing body image dissatisfaction or emotional distress. Chronic bulimia is more challenging to treat due to the ingrained nature of the disorder and the potential for physical and mental health complications.

Distinguishing between short-term and long-term bulimia is crucial in treatment planning. Short-term bulimia may respond well to brief interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), while long-term cases often require a more intensive approach, potentially including medication, long-term therapy, and support from a broader care team. Understanding the duration and severity of the disorder helps professionals tailor treatment strategies, improving the chances of a positive outcome.

Average Duration of the Disorder

The duration of bulimia varies based on individual factors, including early diagnosis, access to treatment, and personal resilience. Studies suggest that, on average, untreated bulimia can last between five to ten years, with a significant percentage of individuals experiencing intermittent relapses even after receiving treatment. Early intervention is often associated with a shorter duration and more favorable outcomes, highlighting the importance of timely diagnosis. Commitment to treatment is key; those who regularly attend therapy sessions and adopt lifestyle changes often see shorter periods of bulimia. Personal factors, such as family support, coping mechanisms, and concurrent mental health issues, also influence the course of the disorder.

Bulimia is often considered a relapsing condition, where symptoms may improve with treatment only to reoccur during periods of stress. The cyclical nature of bulimia can extend its duration, especially if treatment is inconsistent or prematurely discontinued. Recognizing the possibility of relapse can help those affected and their care teams prepare effective strategies for long-term management and support.

Potential for Recovery

Prognosis for Recovery

The prognosis for bulimia recovery is positive, especially with early intervention and comprehensive treatment. Many individuals recover fully or experience significant symptom reduction with evidence-based treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and, in some cases, medication like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The commitment to treatment, the quality of the therapeutic relationship, and consistent family or social support are critical factors in recovery. Studies indicate that individuals who engage in therapy for an extended period, maintain a healthy support network, and address underlying emotional issues have the highest recovery rates.

Factors Affecting Treatment Outcomes

Several factors impact treatment outcomes for bulimia. Co-occurring mental health conditions, like depression or anxiety, can complicate treatment, making it essential for professionals to address these issues simultaneously. Motivation to change is another crucial factor; individuals with a strong desire for recovery are more likely to adhere to treatment plans and make lifestyle changes. Additionally, a supportive environment, whether from family, friends, or community groups, has been shown to improve recovery rates. Access to specialized care also plays a significant role, as individuals who receive treatment from eating disorder specialists often experience better outcomes due to targeted therapy approaches.

Though recovery from bulimia is achievable, it's important to understand that the process is usually gradual, with both setbacks and advancements. Building a resilient mindset, fostering positive coping mechanisms, and maintaining long-term support are crucial elements in achieving and sustaining recovery. With the right support, many individuals lead fulfilling lives beyond bulimia, making early and accurate diagnosis, along with a robust treatment plan, foundational steps toward lasting health and well-being.

Treatment and Medication Options for Bulimia

Bulimia nervosa is a complex eating disorder characterized by recurring episodes of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors, such as purging, fasting, or excessive exercise, to prevent weight gain. A comprehensive treatment plan for bulimia often includes a mix of psychological therapies, medical treatments, nutritional guidance, and supportive care. Each component addresses distinct aspects of the disorder, from underlying psychological triggers to the physical and nutritional deficits caused by the disorder.

Psychological Therapy Options

Psychological therapy is at the forefront of bulimia treatment, focusing on identifying and addressing the emotional and cognitive triggers behind disordered eating behaviors. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective approaches, helping individuals recognize the negative thought patterns and self-destructive behaviors that fuel the disorder. Through CBT, patients learn to challenge their distorted beliefs about body image and self-worth, develop healthy coping mechanisms, and establish a more positive relationship with food.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), another powerful tool, focuses on emotional regulation and impulse control. Given that bulimia often involves impulsive binge-purge cycles, DBT helps individuals manage intense emotions, reduce self-destructive behaviors, and improve stress tolerance. Group therapy offers peer support, allowing individuals to share experiences in a non-judgmental environment and find camaraderie in their shared struggles. Group sessions are effective for decreasing isolation, which is common among those with bulimia, and provide a support system outside individual therapy. Each therapy modality offers specific benefits, and a combination of these can provide a well-rounded approach for treating bulimia.

Medical Treatment and Medications

In addition to psychological support, some individuals benefit from medical treatments, including medications that address underlying mental health issues. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), particularly fluoxetine, are commonly prescribed to help manage symptoms of depression and anxiety, which frequently co-occur with bulimia. By improving mood and reducing anxiety, SSRIs can reduce the frequency of binge-purge episodes and enhance the effectiveness of psychological therapy.

Medications such as topiramate, an anticonvulsant, have shown some promise in reducing binge-eating episodes by stabilizing mood and reducing impulsive behaviors. Nevertheless, medication by itself is inadequate for managing bulimia; it is most effective when paired with therapy to tackle the root causes. Healthcare providers carefully monitor patients on medication to ensure there are no adverse side effects, particularly as individuals with bulimia are often dealing with compromised physical health due to repeated purging.

Nutritional Counseling and Rehabilitation

Nutritional counseling is critical for restoring physical health and rebuilding a healthy relationship with food. In nutritional counseling, dietitians work with individuals to create structured eating plans that promote balanced eating patterns, aiming to prevent binge-eating episodes. This approach helps normalize eating habits, ensuring that patients receive adequate nutrition and avoid dangerous cycles of restriction and binging.

Nutrition education is equally essential, as individuals with bulimia may have misconceptions about food, body weight, and health. Learning about proper portion sizes, nutrient-dense foods, and the impact of restrictive diets on health can empower individuals to make healthier choices. Nutritional rehabilitation is often gradual, helping the body adjust without triggering relapses. This part of treatment also addresses electrolyte imbalances, dehydration, and vitamin deficiencies, all common consequences of bulimia.

Inpatient vs. Outpatient Treatment

The choice between inpatient and outpatient treatment depends on the severity of the disorder, medical complications, and the individual’s support system. Inpatient treatment is recommended for those with severe bulimia, especially if it has led to life-threatening complications like electrolyte imbalances, cardiac issues, or severe malnutrition. Inpatient care provides 24-hour supervision and access to immediate medical interventions, creating a structured environment that minimizes the risk of self-harm.

Outpatient treatment, on the other hand, is suitable for individuals who can manage their symptoms with regular therapeutic support and do not require intensive monitoring. Outpatient programs offer the flexibility to continue everyday responsibilities while attending therapy sessions and medical appointments. Some facilities provide a partial hospitalization program (PHP), a structured day treatment option that bridges the gap between inpatient and outpatient care. This choice depends on the individual’s needs and the specific treatment goals set by healthcare providers.

Prevention of Bulimia

Preventing bulimia involves both societal and individual approaches, especially in adolescents and young adults, who are at a higher risk due to societal pressures and developmental challenges. Schools, families, and communities play a pivotal role in prevention efforts by promoting positive body image and self-acceptance. Educating young people on the dangers of diet culture and the importance of body diversity can help reduce the desire to engage in harmful eating behaviors.

Strategies for Prevention in Adolescents and Young Adults

Prevention strategies in adolescents and young adults should focus on awareness and education. Programs that teach healthy coping mechanisms for stress, frustration, and societal pressures can reduce the likelihood of bulimia developing. Incorporating discussions around media literacy, self-esteem, and realistic body standards in schools can empower young people to question harmful beauty ideals and appreciate their bodies. Interventions should also educate youth about the dangers of fad diets and the importance of balanced eating.

Promoting Positive Body Image and Self-Esteem

Positive body image initiatives help combat the influence of social media and advertising, which often promote unrealistic body standards. Techniques such as self-compassion exercises, journaling, and mindfulness practices can help individuals cultivate a healthier relationship with themselves. Schools and communities can offer programs that support mental well-being, encouraging a sense of self-worth based on attributes other than appearance. These programs work best when they involve both teens and their families to create a supportive home environment.

Role of Family and Friends in Prevention

Family members and friends play a crucial role in preventing bulimia by providing support and promoting healthy attitudes toward food and body image. Family-based support strategies entail informing family members about the indicators and dangers of eating disorders, enabling them to serve as early responders. Loved ones can create a supportive environment by avoiding diet talk, encouraging balanced eating, and fostering open communication. Positive reinforcement and genuine concern can often reduce the stigma around discussing body image issues, making it easier for individuals to seek help.

Complications of Bulimia

Bulimia can have severe physical and mental health complications, affecting multiple organ systems and overall well-being. Understanding these risks underscores the importance of timely intervention and comprehensive treatment.

Physical Health Complications

The physical complications of bulimia are extensive and can include long-term damage to the digestive, cardiovascular, and endocrine systems. Repeated vomiting leads to tooth erosion, esophageal tears, and chronic sore throat, while electrolyte imbalances can cause severe heart irregularities and increase the risk of sudden cardiac arrest. Over time, frequent purging can also result in gastrointestinal issues like constipation, bloating, and chronic acid reflux, and even kidney damage due to dehydration.

Mental Health Risks and Emotional Impact

Mental health complications are pervasive in individuals with bulimia, often including mood disorders, anxiety, and low self-esteem. Depression and anxiety frequently co-occur, exacerbating the cycle of disordered eating and increasing the likelihood of social withdrawal. The emotional impact of bulimia may result in feelings of isolation, self-hatred, and a warped self-perception, which can obstruct recovery progress. Addressing these mental health risks through therapy and support groups is essential for long-term recovery.

Social and Relationship Implications

Bulimia can strain social relationships, as secrecy, guilt, and shame often lead individuals to withdraw from friends and family. The disorder can create a barrier to genuine connection, with many individuals avoiding social situations that involve food or body-focused conversations. In familial relationships, the stress of supporting someone with bulimia can sometimes lead to misunderstandings or tension. Therefore, involving family in the treatment process is beneficial, as it fosters empathy, provides support, and improves communication.

Research and Statistics: Who Has Bulimia?

Bulimia nervosa, a serious eating disorder marked by cycles of binge eating followed by purging or other compensatory behaviors, affects millions of people globally. Yet, understanding its full scope requires a closer look at prevalence statistics, the demographics affected, unique risk factors in diverse populations, and how it intertwines with other mental health conditions. Below, we’ll dive deeply into these aspects, shedding light on who is most vulnerable to bulimia and what challenges they face on the road to recovery.

Prevalence of Bulimia Worldwide

Research indicates that bulimia affects approximately 1-2% of the global population, though rates vary by region, with Western countries often reporting higher incidence due to factors like social media, diet culture, and beauty standards. Studies show that bulimia is one of the most common eating disorders, especially in countries like the United States, Australia, and parts of Europe. However, cases may also be underreported, especially in areas where mental health awareness and diagnostic resources are limited. Variances in cultural attitudes toward body image and food may also contribute to discrepancies in bulimia prevalence rates, making it crucial to recognize that bulimia is likely present in all cultures but reported at different rates.

Statistics on Bulimia Rates Across Populations

In the U.S., the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) reports that approximately 1.5% of American women and 0.5% of American men will struggle with bulimia at some point in their lives. Similarly, studies in European countries reveal rates ranging from 1% to 1.5% in adult women, while countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where data collection is newer or culturally sensitive, tend to report lower numbers, often due to stigma or limited healthcare accessibility. Importantly, bulimia is under-diagnosed across all regions, with hidden cases particularly prominent among men and older adults who might not fit the stereotypical profile of someone with an eating disorder.

Gender and Age Factors

Bulimia most commonly affects young women, with peak onset occurring between ages 18 and 24. However, it is crucial to note that bulimia can impact individuals of any age, with recent studies highlighting increases in cases among older adults and teenagers as young as 13. The majority of bulimia cases occur in females, partly due to societal pressures on women regarding appearance and body size. Despite this, male cases are increasing, particularly among young athletes, models, or men facing specific appearance pressures. Men may also experience unique stigmatization when seeking treatment, leading to further underreporting.

Potential Reasons for Gender Disparities

Research suggests that social and cultural factors significantly impact the gender disparity in bulimia prevalence. Societal ideals often promote slenderness and attractiveness, especially for women, influencing many young women to engage in disordered eating to meet these expectations. For men, societal norms may prioritize muscularity or athleticism, leading to behaviors that overlap with or develop into bulimic patterns. The rise of social media and image-focused platforms has also increased appearance-related anxieties across genders, further exacerbating bulimia risk in young people.

Longitudinal Studies on Bulimia

Longitudinal studies on bulimia reveal important insights into its causes, risk factors, and progression. Studies indicate that genetics, childhood experiences, and exposure to diet culture can all contribute to developing bulimia. For instance, a family history of eating disorders or mood disorders like depression can heighten vulnerability. Studies also show that bulimia tends to co-occur with other mental health conditions, suggesting that early intervention in childhood or adolescence can help prevent the disorder’s progression. Additionally, long-term research emphasizes the chronic nature of bulimia, highlighting the need for ongoing treatment and support even after recovery.

BIPOC and Bulimia

Prevalence Among BIPOC Communities

Bulimia affects people from all racial and ethnic backgrounds, though it has historically been viewed as a “white woman’s disease,” leading to underreporting in BIPOC communities. However, recent research shows that bulimia rates in Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities are comparable to, if not higher than, rates among white populations. Studies indicate that bulimia often goes unreported among BIPOC individuals due to cultural stigma, limited access to healthcare, and underdiagnosis by providers who may not recognize symptoms within these communities.

Unique Risk Factors for BIPOC Individuals

BIPOC individuals may face distinct risk factors that increase their vulnerability to bulimia, including cultural and socio-economic influences. For example, racial discrimination and experiences of marginalization can lead to increased stress, depression, and a desire to exert control, all of which are contributing factors to bulimic behaviors. Additionally, BIPOC individuals may experience unique pressures around body image, with some cultural communities emphasizing specific body ideals or appearance norms that differ from mainstream Western beauty standards. These intersecting factors can heighten the risk of developing bulimia and make recovery more complex.

Barriers to Diagnosis and Treatment

BIPOC individuals often face several barriers to diagnosis and treatment, including lack of culturally competent care, limited financial resources, and fear of stigmatization. In many cases, medical professionals may overlook symptoms of bulimia in BIPOC patients due to stereotypes or misdiagnosis. Furthermore, socioeconomic disparities limit access to mental health services, making it challenging for some to pursue treatment. Addressing these barriers through inclusive health policies and increasing representation in mental health professions is essential for supporting recovery in these communities.

Related Conditions and Causes of Bulimia

Connection with Other Eating Disorders

Bulimia often coexists with other eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Many individuals diagnosed with bulimia have histories of restrictive dieting, which can eventually lead to binge-purge cycles as a means of coping with intense food-related guilt or anxiety. Additionally, individuals with binge eating disorder may develop bulimic behaviors if they attempt to “counteract” their binges through purging.

Substance Abuse and Bulimia

Studies reveal a strong correlation between bulimia and substance use disorders, particularly with alcohol, stimulants, and prescription medications. Individuals with bulimia may use substances to suppress appetite, cope with anxiety, or enhance weight loss, leading to a dangerous cycle where substance abuse worsens bulimic behaviors. This connection highlights the importance of dual-diagnosis treatment approaches that address both bulimia and substance use.

Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Mood and anxiety disorders are commonly linked to bulimia, as many individuals with bulimia also struggle with conditions like depression, generalized anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Emotional dysregulation, or the difficulty in managing intense emotions, often contributes to bulimic behaviors as a coping mechanism. Addressing these underlying mood and anxiety issues is essential in bulimia treatment, as effective management of these conditions can reduce the frequency and intensity of disordered eating episodes.

Summary

Key Takeaways

Bulimia is a widespread yet complex disorder that affects diverse populations worldwide. While young women represent the majority of reported cases, bulimia’s prevalence among men, older adults, and BIPOC communities is rising. Cultural, socio-economic, and environmental factors play significant roles in bulimia risk, particularly among underrepresented populations. Coexisting conditions, like substance abuse and mood disorders, complicate the disorder and underscore the need for holistic, individualized treatment approaches.

The Road to Recovery

Overcoming bulimia is difficult but possible with appropriate support and resources. Treatment often includes a combination of psychotherapy, nutritional counseling, and medical care, all tailored to address both physical and psychological needs. Encouragingly, many individuals find long-term recovery and learn to manage their triggers and emotional challenges through therapy, support groups, and self-care strategies. Building awareness around bulimia, breaking stigmas, and increasing access to culturally competent care can empower individuals on their path to healing, promoting resilience, and well-being across diverse communities.

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQs)

01. What is bulimia prevention?

- Bulimia prevention involves educating people about healthy eating habits, promoting positive body image, and providing early intervention for those at risk. It also includes raising awareness about the dangers of dieting and the importance of seeking help for mental health issues like depression and anxiety.

2. What is the cause of bulimia?

- The exact cause of bulimia is unknown, but it is believed to be a combination of genetic factors, learned behaviors, and environmental influences such as societal pressure to conform to certain body standards.

3. What is the diagnosis of bulimia?

- The diagnosis of bulimia typically involves a thorough medical and psychological evaluation. Healthcare professionals may use interviews, questionnaires, and physical exams to assess eating behaviors, body image issues, and any related health problems.

4. What is treatment for bulimia like?

- Treatment for bulimia often includes nutritional counseling, psychological therapy (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy), and sometimes medication to address underlying mental health issues. The goal is to help individuals develop healthier eating patterns and improve their self-esteem.

5. Which of the following is a symptom of bulimia?

- Bulimia symptoms may involve consuming large amounts of food followed by purging actions like vomiting or laxative abuse, over-exercising, and an obsession with body weight and appearance.

6. What is the best treatment for eating disorders?

- The best treatment for eating disorders typically involves a multidisciplinary approach that includes nutritional counseling, psychological therapy, medical monitoring, and sometimes medication. Each person's treatment plan should be tailored to their specific needs.

7. How can we prevent eating disorders?

- Preventing eating disorders involves promoting healthy body image, encouraging balanced eating habits, and providing support for mental health. It also includes educating people about the dangers of dieting and the importance of seeking help for mental health issues.

8. Which of the following is a common treatment for bulimia?

- Common treatments for bulimia include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), nutritional counseling, and sometimes medication to address underlying mental health issues.

9. How do you diagnose an eating disorder?

- Diagnosing an eating disorder typically involves a comprehensive evaluation by healthcare professionals, including interviews, questionnaires, and physical exams to assess eating behaviors, body image issues, and any related health problems.

*Image credits- freepik*

Important Notice:

The information provided on “health life ai” is intended for informational purposes only. While we have made efforts to ensure the accuracy and authenticity of the information presented, we cannot guarantee its absolute correctness or completeness. Before applying any of the strategies or tips, please consult a professional medical adviser.